India’s milk industry struggles as the climate changes

In a humid, late-July day this year, Chandan Singh went to milk his buffaloes, only to find five of them spewing foamy saliva. The village veterinarian diagnosed haemorrhagic septicaemia (HS), a bacterial disease also known as gala ghotu rog. Treatment cost around INR 15,000 (USD 179), which roughly equates to six weeks of the dairy farmer’s income. Despite this intervention, two of his buffaloes died within days.

“They developed swelling in the throat and the eyes became red. They couldn’t breathe,” Singh says.

Singh, who lives in Punawali Kalan village in the north of India, is not alone in suffering such losses. Around 75 cattle have died within a five-kilometre radius of his village this monsoon. HS thrives in moist and humid conditions. This makes it a recurring challenge for farmers, particularly as climate change increases temperatures and intense rainfall events in the region.

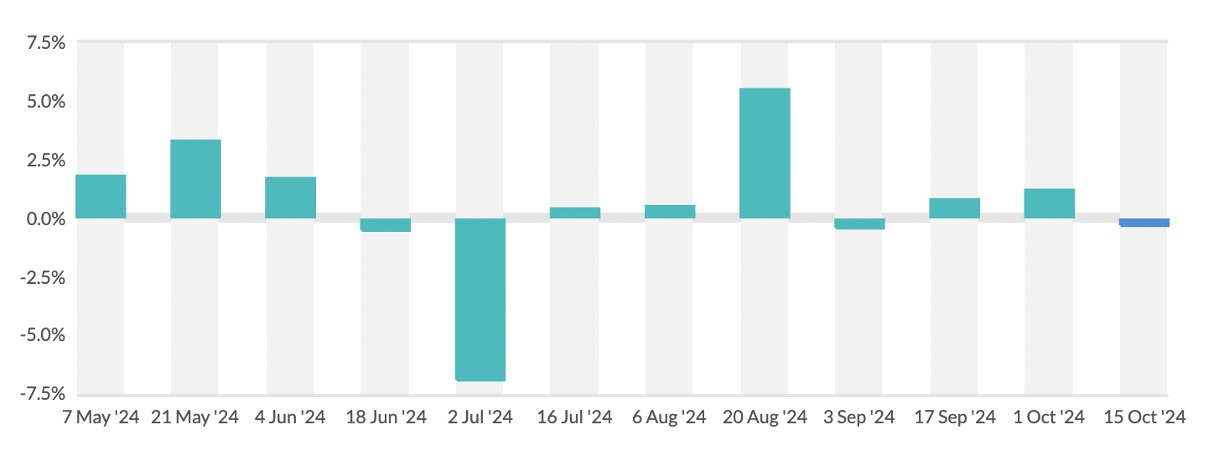

This year, Punawali Kalan’s dairy farmers have also experienced plummeting milk yields due to extreme heat waves. Rajkumar Rajput, another local farmer, saw his daily production drop from 45 to 30 litres as winter became summer. Rajput supplies the daily milk demands of 40 households and says he “had to buy milk to cover the shortfall”.

In 2017, India’s Central Institute for Research on Buffaloes conducted a study on climate change and buffalo farming. It said sudden extreme temperature variations can cause a 10-30% drop in milk production during the first lactation, and a 5-20% drop during the second and third lactations. These impacts continue for 2-5 days.

This challenge is only set to grow. A 2022 study by the Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute estimates that, as temperatures rise, the growing drop in annual milk production in the northern plains – which account for 30% of India’s milk production – could amount to 361,000 tonnes by 2039. Such a drop would represent losses amounting to INR 11.93 billion (USD 142 million).

A 2022 Lancet study warned that, if global greenhouse gas emissions remain high, rising temperatures could cut milk production in arid regions by 25% by 2085.

The direct and indirect threats of climate change

Abhinav Gaurav, a livestock management advisor for the climate action NGO Environmental Defense Fund, says climate change is impacting cattle both directly and indirectly. The animals themselves struggle with intensifying heat and humidity, and the climate impacts also interfere with the production of their fodder, alter their pastures, and increase their exposure to disease.

A 2016 study led by Bengaluru’s National Institute of Animal Nutrition and Physiology suggested most milk production losses were incurred via these indirect climate change impacts. Predominantly, that means shrinking – or simply unavailable – feed and water sources.

Climate change affects forage quality and availability by shifting precipitation patterns, raising temperatures, and altering vegetation. This compounds water scarcity, which is especially harmful to buffaloes because their thick black skin makes them particularly vulnerable to heat stress. “The loss of traditional wallowing ponds exacerbates this vulnerability,” adds Gaurav.

Yunus, another dairy farmer in northern India, has seen fodder prices surge when crops fail in heavy rainfall. “I had to buy fodder at INR 1,700 per quintal, compared to the usual INR 700-800,” he says. This summer, milk output from Yunus’ 30 buffaloes dropped from 200 to 150 litres.

In the dairy sector, milk prices depend on fat and solid-not-fat content. This content decreases in the lean period (April to September) as heat and humidity rise. Climate change exacerbates this by making heat stress and erratic rainfall more likely, meaning less income for milk producers.

An industry blinkered by target-chasing

Launched a decade ago, the Indian government’s National Livestock Mission aims to boost productivity and fodder production in the sector, but it fails to consider the impact of climate change.

Dialogue Earth consulted Namrata Ginoya, senior manager of the Resilience and Energy programme at the World Resources Institute India. She has studied adaptations to climate change in dairy farming, and says farmers are beginning to understand how climate variability and its impacts on rainfall, heat and moisture will affect their cropping systems. On the other hand, she notes there is still insufficient information available to farmers on how rising heat stress could affect their cattle.

“The dairy sector in north and west India now relies on cooperative societies like Amul, which depend on small farmers with few cattle,” explains Ginoya.

India’s remarkable position as the world’s largest milk producer rests on the structure of these dairy cooperatives, as well as a national programme to expand milk production that began in 1970. The majority of milk producers in such cooperatives are small farms with limited resources. “With [the impact of] climate change, many small farmers can no longer afford to keep livestock,” Ginoya adds.

“The government is not yet focusing on climatic variations,” adds Singh. “Right now, the focus is on achieving higher milk production.”

In 2021, the Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying began to implement a national action plan for dairy development, with a goal of doubling 2016’s national milk production rates by 2024. In 2022, Uttar Pradesh published a five-year promotion policy for its milk products and dairy development. Its 11 objectives do not explicitly consider the impacts of climate change. So far, there is little public data available on how these projects have progressed.

Dairy sector emissions: A loop paradox?

Climate change negatively impacts the productive performance of meat and dairy livestock, but this is a two-way relationship: livestock farming intensifies climate change by contributing substantially to greenhouse gas emissions. Compared across a 20-year period, methane emissions (such as those created by livestock digestive processes) have 86 times the global heating potential of carbon dioxide; methane breaks down in the atmosphere after approximately 10 years, while carbon dioxide persists for 300-1,000 years.

Dialogue Earth consulted V Beena, a veterinary physiology professor at the Kerala Veterinary and Animal Sciences University: “In India, carbon emissions from livestock farming may not be as significant as in western countries, where large numbers of animals are raised for meat, leading to high methane emissions. Here, mixed farming, with livestock and plantations, helps in carbon sequestration, making many farms close to carbon-neutral.”

“There is a need for farms to undergo carbon assessments, and a licensing system could ensure that each farm maintains carbon neutrality,” Beena adds.

Tentative solutions

The Indian Council of Agricultural Research launched the National Innovations in Climate-Resilient Agriculture (NICRA) project in 2011. An attempt to mitigate climate change impacts in the agricultural sector, the project focuses on research, technology demonstrations and awareness-raising.

“NICRA has produced valuable findings, such as identifying genetic traits in indigenous cattle breeds for better productivity and resilience to weather conditions,” says Gaurav. “It has piloted studies in 151 climatically vulnerable districts with promising results, but further knowledge dissemination and policy integration is lacking.”

In the meantime, there are few ways for farmers like Chandan Singh to recoup their losses. The government’s livestock insurance scheme only covers losses attributable to death.