Leading into the 2023 elections one of the promising announcements that came from National was the intent to open negotiations with India and achieve a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) – and dairy was to be included. It was described by National as a “major strategic priority”.

At the time many (myself-included) poured cold water on the plan as a broad-based FTA was thought to be unlikely to succeed. Even the Australians who had just signed a reasonably broad-based FTA failed to get dairy included.

Since being elected the new New Zealand government has doubled down on its plan with Todd McClay suggesting that locking in a trade deal with India within three years was possible. While a FTA with India is a laudable goal many have seen that while some lesser agricultural goods may be seen as attractive to India, horticultural goods stand out as being the prime candidates, including dairy will be a major stumbling block.

So, with this as a backdrop, a closer look at the Indian dairy industry is due, if only to see how will it meets the requirements of the world’s largest population.

India also has the world’s largest dairy cow population. Last count cow numbers were 72 million to supply its 1.4 billion people. So, one cow supplies the milk to 19+ humans. So there are millions of [voting] dairy farmers.

New Zealand isn’t unique being unable to get any volume of dairy products into India, and in fact in US$ terms the value of what is imported has decreased in recent years going from a tiny US$45.2 mln in 2021/22 down to a mere US$19.4 mln in 2022/23. Its greatest imports came in 2021 at US$ 252 mln (not inflation adjusted). So, as can be seen nobody is getting much dairy over its border.

Perhaps not surprisingly the price of dairy staples within India have leapt up there. The lack of imports is not the only factor leading to a recent reduction in available volume of dairy products in India. The Covid lockdowns led to a decline in demand and price which in turn led to some dairy farmers exiting the industry.

Climate conditions have also created poor growing seasons for cow feed crops pushing up costs and discouraging others to re-enter. A cattle disease “lumpy skin” is also said to have created a higher cull rate of infected animals reducing the herd size.

Some sources have said that there was a jump in dairy imports in the early part of last year (2023) as import restrictions were temporarily lifted. These numbers do not yet appear to have flowed through to official published data as yet but would make sense, if it were not for the fact that India is also exporting large volumes of dairy products.

The latest numbers tell that US$$285 mln worth of products were exported mainly to Bangladesh and Middle Eastern countries – with some also going into the USA. Most exports are in the form of milk powder but a little as liquid milk. Part of the limitations of liquid milk volumes is due to the presence of foot and mouth disease (FMD) in the herd meaning it doesn’t meet international protocols.

There is an aim to have India FMD free by 2030 through vaccination but with the average herd size around 2 cows (so 35 million ‘herds’) there are a lot of herds to get around.

So, like much to do with politics, India is full of contradictions. Regarding keeping dairy away from FTA’s in general the Indian government’s feeling appears to be that the dairy sector is “the most important sector to boost the Indian rural economy”. So, the Indian government is keen to see milk prices rise. Presumably, if by market conditions then government doesn’t have to get overly involved handing out cash. Having said this, at least in some provinces subsidies are available to boost production. In Uttar Pradesh, which is the highest milk producing state with 18% of total milk production, farms of over 25 cows can receive subsidies of up to 50% of the cost to increase investment resulting in greater production. India is quite unlike China (which was well behind the ball with dairy production and hence why they were likely keen to have it included in the FTA with New Zealand).

India has the world’s largest herd, already Indian’s consume about 25% per person above the world average amount of dairy products on a daily basis. This indicates that additional production is likely to end up on the international market.

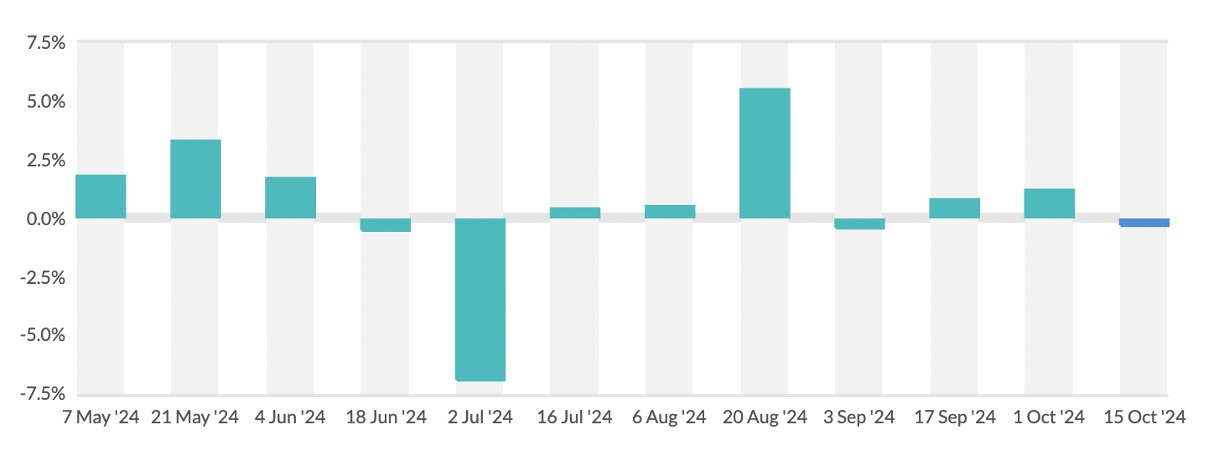

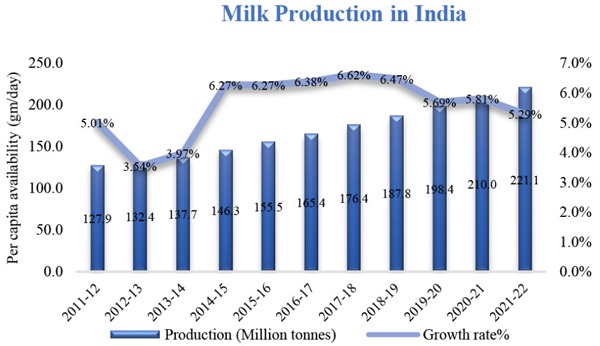

As the graph below shows, there has been considerable increase in production with the recent downturn seen by India as a temporary situation, hence a temporary relaxing of some imports. The numbers and widespread integration of dairying into the rural landscape means that with the right tools and incentives India has the potential to increase supply considerably.

So, I still haven’t changed my opinion that we won’t see any relaxing of potential FTA grounds with New Zealand (or Australia) any time soon.

Hanging our FTA negotiations hat onto dairying, especially when we don’t (unlike Australia) have much of what India needs means to me that including dairying will act as an obstacle to gaining benefits for other sectors.

Perhaps we should be more concerned about India increasing its role as an exporter.