The latest dairy market review report by FAO for the year 2023 unleashed some interesting insights. Three trends were noticed which are worth sharing .

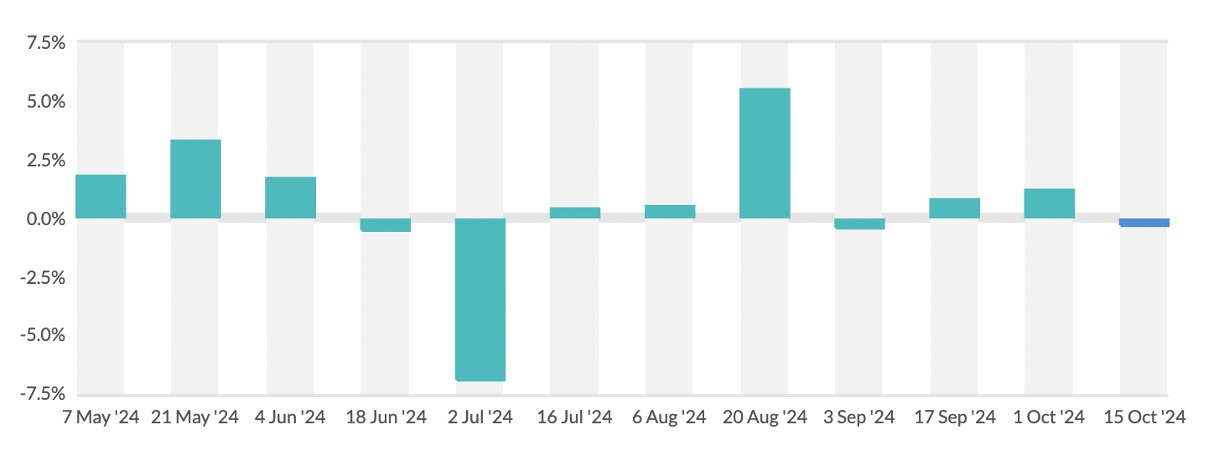

1.In 2023, the FAO Dairy Price Index averaged 123.7, down 17.3% from 2022.

2.In 2023, global milk production rose by 1.5% to 965.7 million tonnes, driven mainly by growth in Asia, accounting for 46% of global output.

2. In 2023, international dairy product exports totaled 84.7 million tonnes, marking a second consecutive year of decline. However, the year-on-year decrease was less severe at 1.0%, compared to 4.3% in the previous year.

In nut shell 2023 was a unique year in which Dairy prices weakened ,milk production expanded but dairy trade contracted globally.

In 2023 another report got my attention. This report “Australian Food Story: Feeding the Nation and Beyond” was an inquiry into food security in Australia. Australia has a long history of dairy development. The Australian dairy industry originated in 1837 in south region with European settlers producing milk, cheese, and butter for the community, mainly in the Adelaide Plains and Adelaide Hills. Let’s glean valuable insights from this report and apply the lessons to the Indian dairy sector.

In the 2021–22 period, Australia’s dairy sector yielded approximately 8.5 billion liters of milk from 1.34 million cows, valued at $4.9 billion at the farmgate. This marked the industry’s lowest output since at least 1996–97.

According to Australian Dairy Farmers Ltd., this decline began after deregulation in 2000 and a shift away from bulk commodity dairy exports. Factors contributing to this downturn include rising input costs, stagnant productivity, decreased export market share, social acceptance challenges, shifting consumer preferences, alterations in production systems, and the impact of climate change.

In September 2020, the Australian Dairy Products Federation (ADPF) announced the launch of the Australian Dairy Plan, aiming to bolster the industry’s profitability and confidence for the future. The plan set an ambitious target of boosting milk production to at least 9.6 billion liters by 2024–25, generating approximately $500 million in additional value at the farmgate. However, the ADPF reported that despite offering record high farmgate milk prices to farmers, the anticipated increase in raw milk production has not materialized.

The report further addd that “The dairy processing sector creates $16 billion in revenue annually, contributing $12.4 billion to gross domestic product.This more than triples the value of raw milk between farmgate and the consumer.There are about 200 processing companies, although ten diary manufacturers process most of the milk”.

Per capita, Australians consume approximately 93 liters of milk, though this has seen a recent slight decline. Consumption trends within the domestic market vary across different dairy products, mirroring shifts in consumer preferences and food trends. Notably, there’s a rising popularity in plant-based alternatives, including alternative milks.

In 2021–22, imports of dairy products amounted to 19% of Australian milk production. This marks a notable rise from 9% in 2006–07. Projections indicate that this trend will persist, with dairy imports forecasted to surge to over 25% of production by 2030.

The dairy sector faces a range of challenges, but probably none greater than raising the level of raw milk production. As the ADPF ( Australian Dairy producers Federation) put it:

Australia currently produces enough milk to meet domestic demand for drinking milk, with excess and imported product enabling manufacturers the choice to divert milk into higher value dairy products. But as raw milk production continues to decline and input costs continue to rise, the risk and reliance on imported dairy products could escalate and hence a need to balance and solve for both.

This lends to the question ‘what is the ideal level of “self-sufficiency” to best manage dairy production costs and remain cost competitive, while assuring security of supply?

Lessons from Australian dairy sector for India

India, the world’s largest milk producer, is on a path of aggressive growth. However, doubts arise about actual milk production due to data from the NSSO on monthly per capita expenses on milk and milk products. These numbers suggest total milk consumption ranging between 125-170 billion liters, compared to the reported 220 billion liters. The Indian dairy sector grapples with the problem of plenty. Whenever milk production increases, farm gate prices dip. There’s a lack of mechanisms to improve situations for farmers, except for milk subsidies, which are mostly limited to farmers linked to state dairy cooperatives. The bigger issue lies with farmers who don’t receive these subsidies, posing a challenge for the entire farming community.

Subsidies aren’t just creating a problem of a level playing field for processors; they’re also discriminatory against farmers, especially women in dairy cooperatives. In Australia, despite having top-notch technologies, government support, high-quality milk, and global product acceptance, farmers are showing indifference to this historical vocation. This indifference is driven by high input costs and the inability of local processors to manufacture value-added products without competitive imported dairy products.

Comparing this situation with the Indian dairy sector, we lack both good quality milk and matching MRPs of dairy products for processors to make significant profits, even by selling value-added products.

The dairy processing sector in Australia creates $16 billion in revenue annually, contributing $12.4 billion to gross domestic product.This more than triples the value of raw milk between farm gate and the consumer.Still large processors like Lactalis, Saputo and some other national brands hav closed their operations as milk production is shrinking.